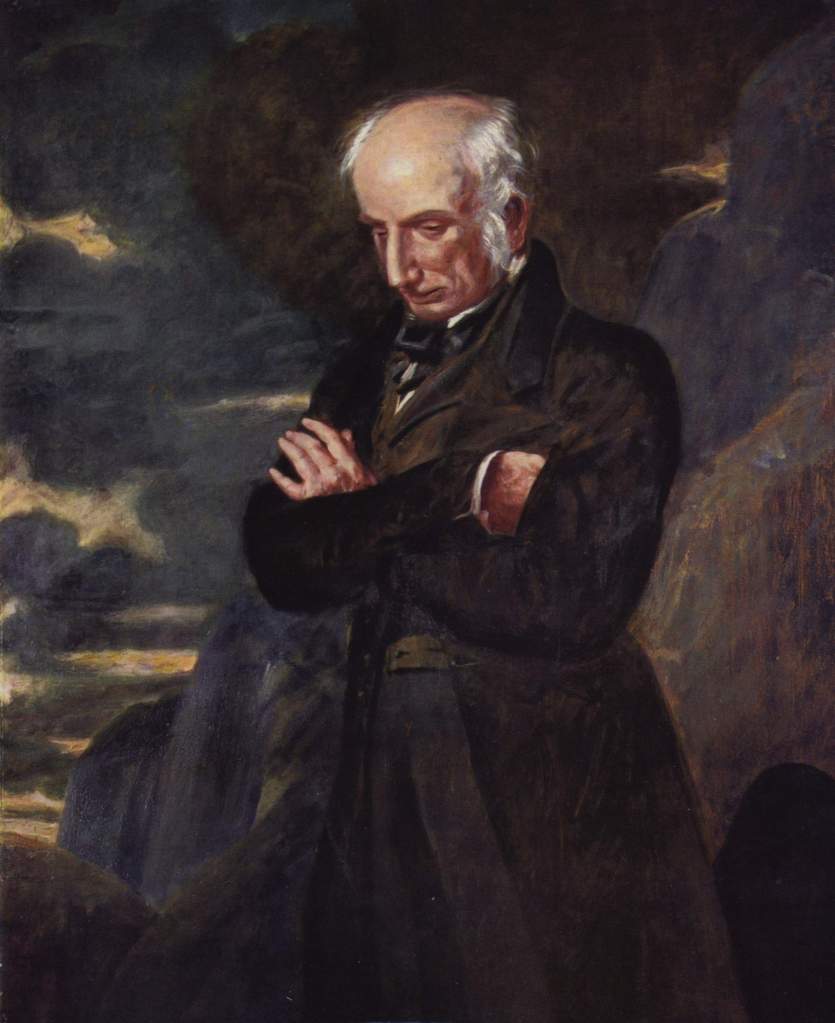

WILLIAM WORDSWORTH

The High Priest of Nature (Who Hated Tourists)

William Wordsworth (1770–1850) is often remembered as the grandfather of the English Romantic movement—a man who spent his life wandering the Lake District, looking at daffodils, and feeling “feelings.” But to dismiss him as a mere flower-gazer is to miss the point. Wordsworth was the first man to look at the Industrial Revolution and realise that “progress” was going to cost us our souls.

Born in the lush greenery of Cumberland, Wordsworth came of age during one of the most chaotic moments in European history. While nature was busy showing off waterfalls and skylarks, humanity was busy chopping down forests, choking cities with soot, and marching armies across the continent in a little political experiment called The French Revolution.

The French Revolution: The Bad Breakup. As a young man, Wordsworth caught the revolutionary fever. Who wouldn’t be seduced by the slogans of liberty, fraternity, and equality? It sounded fresh, radical, and infinitely more alive than a British Parliament dozing over its midday brandy. He went to France, fell in love with the ideals (and a Frenchwoman), and believed the world was being reborn.

But political romance sours quickly. The Revolution devolved into the Terror—heads literally rolling in the streets, dreams of utopia curdling into nightmares of mob rule. For Wordsworth, this was a betrayal of the highest order. He watched his hero tear off a mask to reveal a monster. Disillusioned, he retreated to England with a new conviction: true revolution wasn’t found in the guillotine, but in the mind. And the best place to fix the mind was—where else?—the mountains.

The Lake District: Nature as a Cathedral. If the Revolution broke his political faith, the Lake District restored his spiritual one. To Wordsworth, hills and valleys weren’t just “scenery”; they were moral instructors. No need for kings or committees here—just rivers and stones teaching humility. He insisted that being attentive to nature made a person wiser, gentler, and less obsessed with accumulating wealth.

For Wordsworth, the cure for civilisation’s toxic ambition wasn’t a new law; it was touching grass. Literally.

Of course, while he was scribbling odes to clouds, the Industrial Revolution was spinning cotton mills and shoving peasants into crowded slums. The Lake District became his counter-argument to progress: a sanctuary of silence in a world getting louder by the day.

The Irony of the Railway. Here is where the “High Priest of Nature” gets complicated. Wordsworth loved the solitude of the Lakes so much that he wanted to keep it entirely for himself.

In his later years, he campaigned fiercely against the expansion of the Kendal and Windermere Railway. His argument wasn’t just environmental; it was snobbish. He essentially argued that the unwashed, working-class masses from the industrial cities lacked the “refined sensitivity” to appreciate the view. If the poor came to the Lakes, he feared, they would just clutter up the place with their noise and their cheap picnics.

The irony is sharp enough to cut yourself on. Wordsworth, the champion of the common man’s soul, fought to keep the common man out of his garden. He wanted nature to be a cure for the industrial worker, provided the worker didn’t actually show up to take the medicine.

Legacy: The Sanctuary and the Gift Shop Two centuries later, Wordsworth’s nightmare has largely come true, partly because of him. His poetry made the Lake District so famous that it is now overrun not by factories, but by the very tourists he despised, all clutching guidebooks and buying “Daffodil” tea towels.

Yet, his core warning remains terrifyingly relevant. Wordsworth’s anxiety that technological progress would drain not only landscapes but also human interiors is poignantly expressed in his poem “The World Is Too Much with Us” (1807), where he laments: “The world is too much with us; late and soon, / Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers.” Through these lines, he articulates his fear that society’s obsession with material accumulation would sever our connection to nature and diminish our spiritual vitality.

If he were alive today, watching us scroll through high-definition photos of mountains while sitting in fluorescent-lit cubicles, he wouldn’t be surprised. He would just shake his head, mutter something about how we traded our hearts for a machine, and go for a very long, lonely walk.