William Blake: The Prophet Who Saw Through the Smoke

William Blake was never fooled by the shiny promises of the Industrial Revolution. While others in late 18th-century England gazed in wonder at the new machines and the chimneys belching out what they called “progress,” Blake was already writing their epitaph. The factory owners thought they were building an empire of steel and soot; Blake saw “dark Satanic mills” chewing up children, landscapes, and imagination alike. In a world eager to worship the machine, he dared to ask the impolite question: at what cost? A question his contemporaries politely ignored, too busy applauding themselves for having replaced human misery with mechanical efficiency.

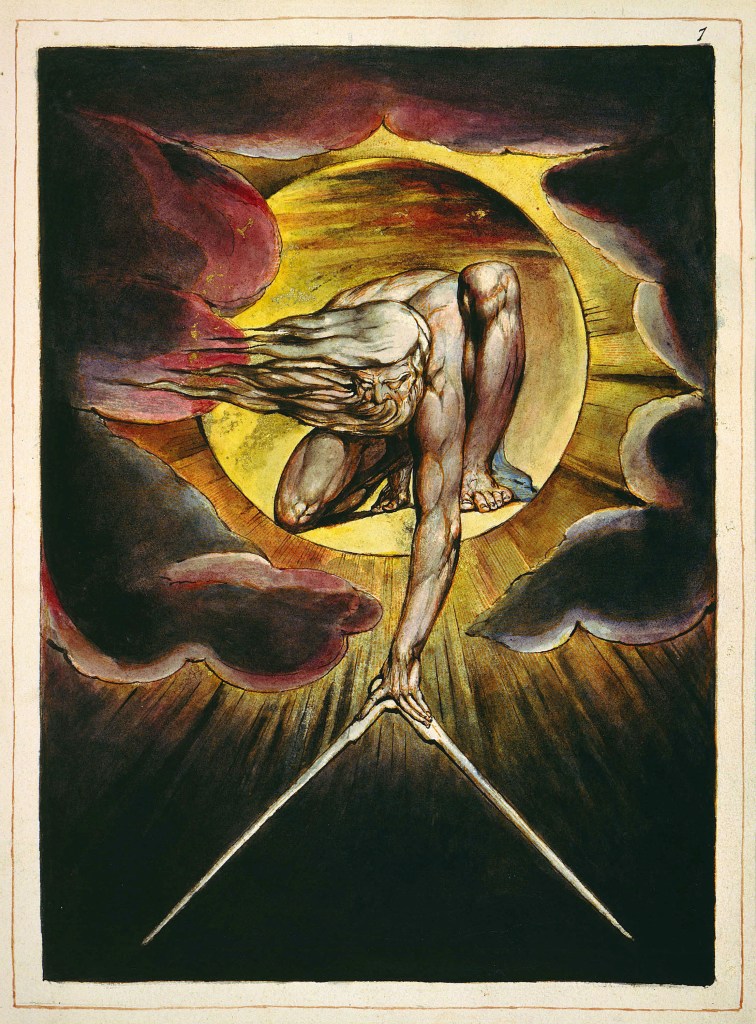

Blake belongs firmly to Romanticism, but he was not the sort to sit quietly in a meadow, jotting down how pretty the daffodils looked. No—he was angrier, stranger, and for that reason, sharper. This was a man who, from the age of nine, claimed to have seen a tree filled with angels on Peckham Rye, their wings sparkling like stars. His neighbours, of course, saw the same tree and concluded it was… a tree. Blake wasn’t a lofty academic; he was an engraver, a craftsman who worked with his hands. He fought back against the cold, rational worldview of his time not with simple poems, but by inventing a whole cast of cosmic entities for his own celestial soap opera—figures like Urizen, the tyrannical god of reason, and Los, the spirit of creative imagination. He wasn’t just writing poetry; he was mapping the geography of the human soul, a pastime much less lucrative than mapping railway lines but infinitely more honest.

His vision of innocence was not just a sentimental glance at cherubs and lambs. His Songs of Innocence depicts a state of pure, unified vision, where a child can ask “Little Lamb, who made thee?” and know the answer is benevolent. But Blake was no sentimentalist. He placed it side-by-side with Songs of Experience for a reason: to show us that innocence is constantly under siege. In the world of Experience, the sweet lamb is replaced by the terrifying, magnificent beast of “The Tyger,” forged in the dark furnaces of a fallen world. This is a London of chartered streets and chartered rivers, a place where people are trapped by the “mind-forg’d manacles” of a society all too willing to do the corrupting. However, it did so with admirable efficiency and nearly industrial-grade enthusiasm.

It is easy to forget how radical Blake really was. At a time when England congratulated itself on the march of industry—rails laid across the land, furnaces roaring like triumphal hymns to progress—Blake looked at the children scrubbing chimneys and wondered whether this was paradise or perdition. His contemporaries assured him it was paradise, though they tended to say so while coughing up soot. For him, the machine was the physical manifestation of his demon Urizen. The “dark Satanic Mills” weren’t just a complaint about smoke; they were about the spiritual factory—a system designed to turn people into cogs. The damage report was, in Blake’s eyes, total:

He saw the imaginative spirit of the child chained to the repetitive rhythm of the machine—a marvellous innovation in psychological suppression. He saw people reduced from individuals to components, their worth measured not by spirit but by output. And finally, he saw a society built on a logic that treated empathy and soul as minor sacrifices in the name of progress.

Looking back, we might almost laugh—bitterly—that his warnings were so quickly brushed aside. Two centuries later, we too live among “dark Satanic mills,” though ours glow with screens instead of coal furnaces and run on data instead of steam. Blake didn’t need to see a smartphone to understand the tyranny of a screen; he would have recognised it instantly as a brilliant advance in self-imposed surveillance. The relentless 24/7 news cycle, the social media algorithm that demands conformity for validation, the “hustle culture” that rebrands exhaustion as ambition—these are his prophecies made real. They are the modern machines that grind down our imagination and demand we think and feel within the prescribed lines. A triumph of progress, really, if the goal was to mechanise the human spirit without ever building a single gear.

Blake’s greatness lies in his ability to see what others refused to notice: that machines alone do not liberate, that industry without humanity is savagery in disguise. And he said it with a prophetic voice, half ferocious, half visionary, always unwilling to flatter the self-satisfied, which undoubtedly made him unpopular among the self-satisfied. His poetry refuses to bow to the age of reason or to the age of wheels. Instead, it insists on imagination, on soul, on the sacred spark that no factory line could ever reproduce.

He was, in truth, a prophet. Pity we’re still not ready to listen—though we’ve become very efficient at pretending we are.